Deciding to guide her own death

ALS patient Angie Bloomquist is cared for by Estella Ganuza, left, her morning caretaker and a licensed vocational nurse, and Joy Hawkins, a certified home health aide, in her San Pedro home. Bloomquist wants the state to let her die through doctor-prescribed medication.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)Former social worker Angie Bloomquist was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis less than two years ago. In her final days, paralyzed and unable to speak, she finds herself pushing more than ever — for the choice to die through doctor-prescribed medication.

A photograph of Fred and Angie Bloomquist from the couple’s earlier days sits on a desk inside their San Pedro home. “I’ve had some deliriously happy times in my marriage,” Fred says. “And I know that those moments, unlike the human body, are everlasting.”

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

In the television room at their San Pedro home, Fred Bloomquist gives water to Angie through her feeding tube. She says she knew long before she was diagnosed that she would want to hasten her death if she became severely incapacitated.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Fred Bloomquist has a quiet moment on the front porch of the San Pedro home he shares with his wife, Angie, and their son, Andres. “I’m not going to reduce her to a few fanciful stories,” Fred says of Angie, who has Lou Gehrig’s disease. “She was too vast, too great. She was a tidal wave.”

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

Angie Bloomquist’s mother, Alma Martinez, 75, strokes her daughter’s hair as she takes a nap. “It’s like a tornado ripped through our home,” Angie says of her incurable illness. “And destroyed everything we built.”

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Andres Bloomquist, 11, center, hangs out after school with his friends, twins Adrian, left, and David Rivera. When Angie’s speech went away about six months ago, she felt Andres begin to drift from her. Maybe it’s his age. Maybe he just doesn’t know what to say or how to say goodbye.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Estella Ganuza, left, Angie Bloomquist’s morning caretaker, brushes Angie’s teeth during the morning routine -- a nearly three-hour process that includes bathing, dressing and getting fed through a tube. Angie’s loved ones have stitched together a round-the-clock schedule of care.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Clothes for the day, including a diaper, are laid out on the end of Angie Bloomquist’s bed as she waits to be dressed by her caretaker. Angie’s worst fear, she used to tell everyone, was losing her ability to speak. How would she connect to the ones she loved the most?

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

“I recently told the hospice chaplain that I felt like I was living the life of a butterfly backward, once independent and now confined to this cocoon which is my body,” Angie Bloomquist wrote in a statement she prepared for a lawsuit she joined, aiming to legally protect physicians who administer lethal doses to mentally competent, terminally ill patients.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

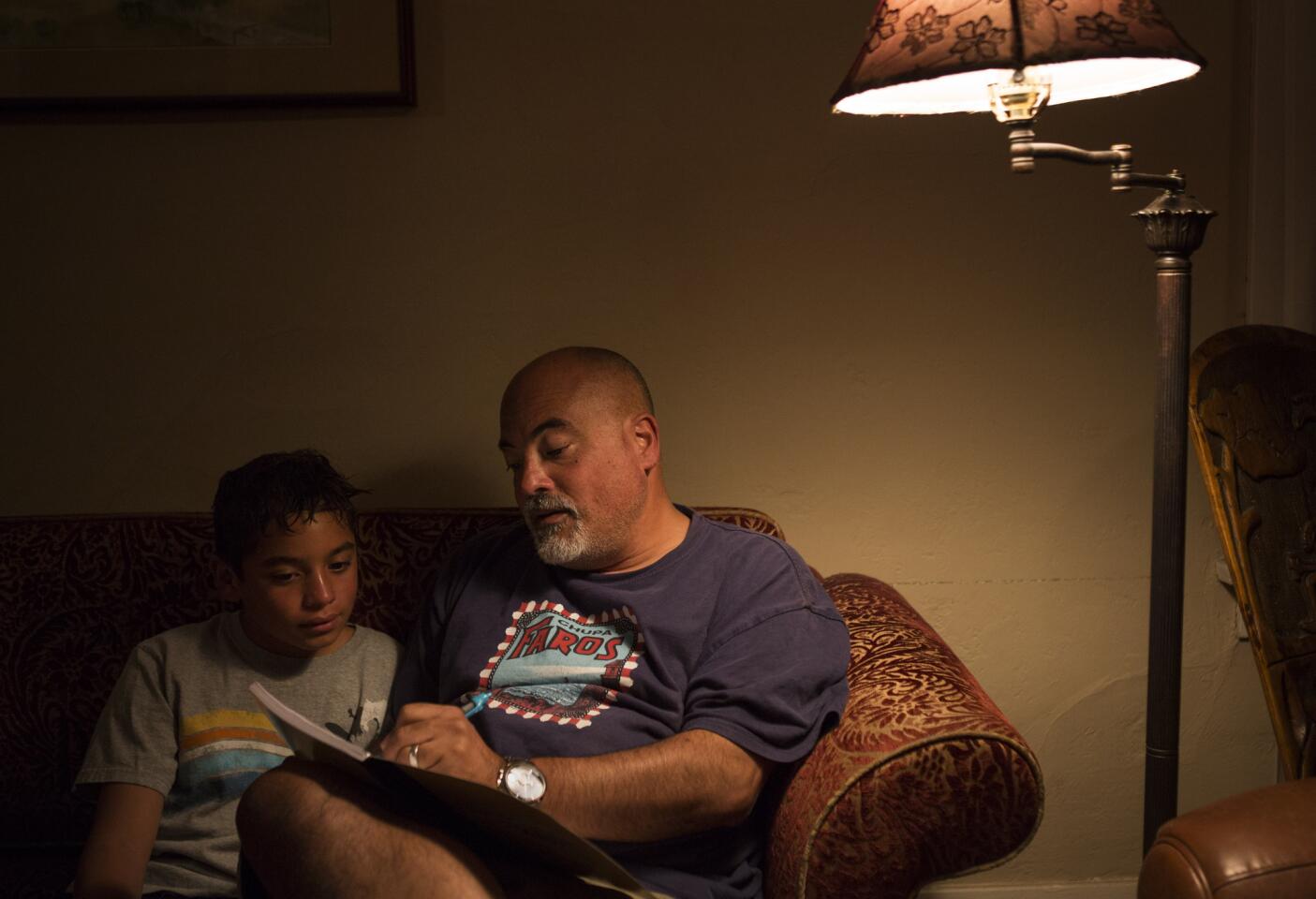

Fred Bloomquist helps his son, Andres, 11, with his homework in their San Pedro home. Andres goes to therapy, at Angie’s request. He says he’s proud of his mother, above all else, “for putting up with me.” After school each day, he bolts through the front door, straight into the television room. “Hi, Mom!” he says.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Fred Bloomquist touches the cheek of his wife of 15 years, Angie, in their San Pedro home. “She’s my everything,” Fred says. Soon after Angie was diagnosed, he organized a ceremony to renew their vows. Beneath two white ash trees in their backyard, his wife giggled as he tried to explain, using the lyrics of his favorite love songs, how much he loved her.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)