- Share via

For the first time in nearly 40 years, never-before-seen images documenting the making of “La Bamba” will be released, giving fans a behind-the-scenes look at the production of one of the most notable U.S. Latino films of all time.

Los Angeles-based publisher Hat & Beard Press announced the June publication of “La Bamba: A Visual History,” which will feature black-and-white photographs by film set documentarian Merrick Morton. The book will include essays by music writer RJ Smith and film journalist Carlos Aguilar (Aguilar is a regular Times contributor).

Written and directed by Luis Valdez, the 1987 biopic chronicles the rise of Pacoima teen rocker Richard Steven Valenzuela, better known as Ritchie Valens, before his untimely death in a 1959 plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa. With a fully stacked Latino cast and crew and a major studio — Columbia Pictures — backing the production, the film was unprecedented for its time.

Nearly 40 years after its theatrical release, ‘La Bamba’ is being remade, but the film’s original director and writer questions why rock ’n’ roll star Ritchie Valens’ life is being told, again.

“La Bamba” exceeded box-office expectations, crushing Hollywood’s belief that Latino-focused projects could not draw an audience. In 2017, “La Bamba” was added to the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress.

Morton credits the beloved movie for kick-starting his successful career shooting still photography for film productions. (He also worked on “Blood In Blood Out,” “Fight Club” and “The Big Lebowski,” among others.)

A street photographer at the time, Morton found his way onto the set serendipitously. His cousin, a hairdresser to film producer Taylor Hackford, showed Hackford some of Morton’s photos of Los Angeles gangs in the 1980s.

Though the studio had already hired a still photographer to capture scenes for promotional use, Morton was brought on board to serve as the production’s documentarian for the 10 weeks of filming. Morton says he took more than 2,500 stills, most of which have been stored away in a filing cabinet for nearly 40 years.

“[Hackford] thought it’d be interesting for someone to photograph a film who hadn’t worked on a film set before,” said Morton.

Before the release of “La Bamba,” very little public information about 17-year-old Valens existed beyond his eight-month musical career with Del-Fi Records and his three albums, two of which were released posthumously.

Still, Valens’ impact as one of the first Chicano rock ’n’ roll stars piqued the interest of filmmaking brothers Luis and Daniel Valdez, who, on the heels of their 1979 “Zoot Suit” Broadway debut, were already looking for their next project. During opening night at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York City, the two overheard a mariachi on 7th Avenue playing “La Bamba,” the Mexican folk song that Valens adopted and which put him on the charts.

“From that moment on, we decided that our next project would be ‘La Bamba,’” said Luis Valdez.

But Daniel had been thinking about Valens’ story long before then. He mentioned the idea to Hackford while they were working on Valdez’s 1973 “Mestizo” album — though at that point it was just a dream.

But with no biography of Valens around at the time, Daniel spent years looking for a direct tie to the musician. Miraculously, in that five-year search, he came into contact with biker Robert “Bob” Morales — Valens’ brother — at a saloon near Watsonville, Calif. Morales then connected him to his mother, Connie Valenzuela.

After making initial contact with the family, Daniel revisited the idea of “La Bamba” with Hackford, who had gained traction after directing “An Officer and a Gentlemen” in 1982, one of the top-grossing films that year.

“Danny called me and said, it’s time to make ‘La Bamba,‘” said Hackford, who was the main link to Hollywood.

Despite the family’s initial skepticism about turning their personal tragedy into a movie, Hackford was able to secure the rights to the film from Valens’ mother.

“When we make this, we gotta make the best film possible,” said Hackford. “Not a nursery rhyme, not a comic book that’s not telling the truth, and [Connie] trusted me.”

With the family’s help and permission, Luis Valdez penned “La Bamba,” weaving in the familial storyline to add depth to the famed singer’s life.

“The more I talked to Bob, the more I realized that this was a [story about a] relationship between two brothers,” said Luis Valdez. “Their mother, Connie, had also been involved in pushing Ritchie to get him the right exposure. I don’t think the movie could have been done without the cooperation of the family, without their honesty and their willingness to cooperate.”

Hackford, who also directed “Blood In Blood Out,” said that Morton’s collection of images was “a valuable document” for what he deems a very special project.

“In the sense of who we put together — the cast, Luis and [Daniel Valdez] and so many people who got their first chance to make a feature film in Hollywood,” said Hackford. “And [Morton] documented that in the photographs, so you can feel and see that kind of passion in those stills.”

To this day, Morton’s favorite photographs are those with both cast members and Valens’ relatives,, who were on set and appeared in some scenes. One of the shots shows two of Valens’ sisters, dressed as extras for the film, holding a photo of their brother.

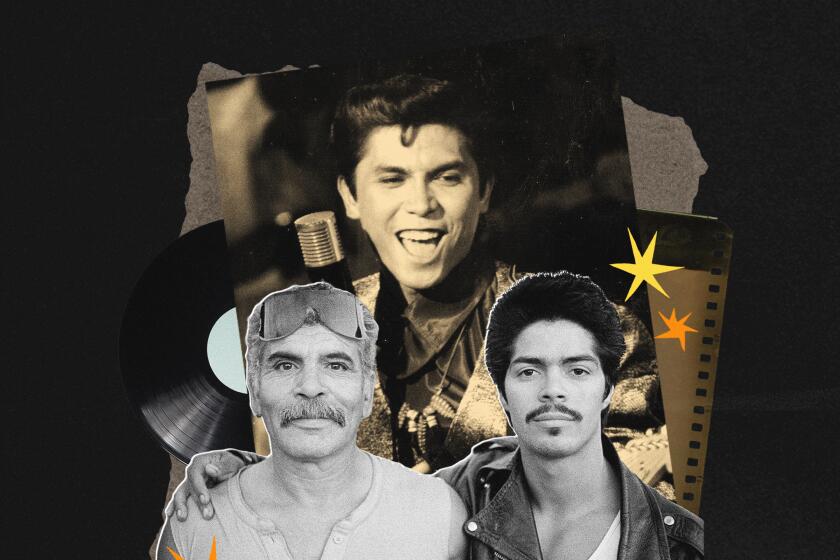

Over the years, Morton has looked back to his time with “La Bamba,” uploading photographs on Instagram, including a side-by-side portrait of Valens’ brother Bob Morales and Esai Morales (no relation), who plays him in the film.

“Everybody sort of blended into one family. I never viewed the actors as separate from anybody,” said Morton.

Many of Morton’s social media followers have called for more insights on the making of “La Bamba,” which has propelled this new coffee-table art book release of “La Bamba: A Visual History.”

Though “La Bamba: A Visual History,” will only showcase a fraction of Morton’s work, he’s hopeful that it will capture the essence of what it felt like to make the film alongside Valens’ family.

“I think that was the part that sort of created something that was real. It’s because you had the family there at the time,” said Morton.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.