People used to buy homes through catalogs. Could that idea help Altadena?

- Share via

Much of Altadena’s rich architectural history was destroyed in hours. English Revivals. Spanish Colonials. California bungalows. Janes Cottages. Neighborhood landmarks and spaces that protected generations of families in the mountain-framed town — all gone in an inferno.

What if there were a way to rebuild the community with respect to what was lost? As residents continue to imagine what Altadena’s future could look like after the Eaton fire, and fight to preserve its legacy from mass development, dreamers have begun mapping plans that would pay honor to homes dating back to the past century.

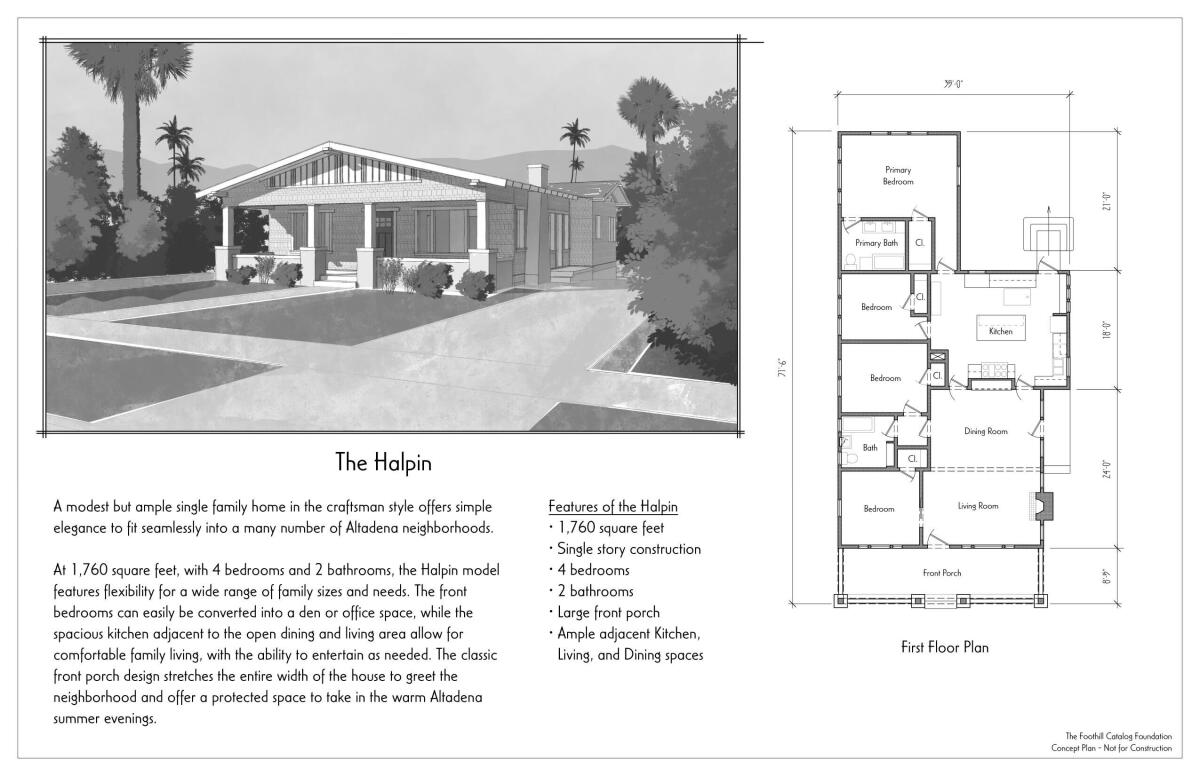

Inspired by early 20th-century Sears catalogs that allowed customers to pick a house design that was sold and shipped as a kit, local architects founded the Foothill Catalog Foundation in the aftermath of the fire. The idea behind the nonprofit is to develop a variety of home designs with pre-approved plans that reflect Altadena’s history.

Altadena’s eclecticism and independent spirit drew residents. After the Eaton fire, they face a crossroads over whether to stay and rebuild their community, or leave.

Design ideas so far include Mediterranean, Craftsman, mid-century and Janes Cottages — derived from a neighborhood of English- and Spanish-style homes built by Elisha P. Janes in West Altadena in the early 1920s. The foundation’s hope is that a simple process to help people rebuild could keep the community intact.

“In Altadena, where there’s so many multigenerational homeowners, a lot of people who might be underinsured or just not insured at all, will likely not have the resources or the emotional bandwidth to go through the process of doing a custom rebuild,” said Sigler, 28, who co-founded the volunteer-run nonprofit with her partner and fellow architect Alex Athenson. “Some people will be able to do that — but a lot of people won’t.”

The pair live in northwest Pasadena at the border of Altadena. Their home survived the fire, but their neighborhood was gutted.

“Being a part of this community, we really saw and understood how devastating this was for Altadena and for everyone who lost their homes,” said Athenson, 30. “That’s kind of what drove us to try and find our place as architects and figure out what we could do to serve the community as a whole.”

Working in tandem with engineers, builders, local government and community groups, the group has started to connect with residents eager to get back — even if it takes years.

Callum Hanlon, who lost his home on Poppyfields Drive, was in the process of building an ADU on his property for in-laws to visit. He knows first-hand that construction projects can be arduous, from bidding on a contractor, to sorting out design plans and materials. He believes that a pre-planned design would significantly cut down the time and costs.

The Eaton fire destroyed thousands of structures in Altadena and Pasadena. Now, residents grapple with how they can afford to rebuild.

“I would rather have that than be going back and forth with the county and spending upwards of $60,000 on an architect in a year of revisions to get the perfect home,” he said.

Hanlon, 36, said his family moved to the area before his first child was born four years ago. The quaint community, and the trees, drew him to Altadena and he doesn’t want to leave it now.

“I want to return,” he said. “Altadena gave us the best of both worlds in having this tight-knit community where we feel comfortable raising our kids and relying on neighbors and other members of the community and being around people who seem to want the same.”

Hanlon has been spreading the word about the Foothill Catalog and recently coordinated a Zoom webinar Thursday for dozens of residents interested in learning about the foundation. Sigler explained the general concept and answered questions related to mission and price.

“If something gets built multiple times, then you can start to think about pre-fabricating and bulk ordering, which are all things that can chip away at that cost,” she said. “While I can’t give a specific cost for these homes, we’re confident that given all of those factors, it will be a more affordable option.”

The nonprofit is still in the early stages of planning. They have met with L.A. County’s Planning and Building and Safety departments, Sigler said, and are figuring out if insurance carriers will have any requirements they would need to take into consideration with plans. Their intention is to develop a framework soon.

A recurring idea among residents is that a successful rebuild must be community-driven in order to protect the legacy of the town, which includes historically Black neighborhoods, and to ensure that residents aren’t pushed out. Altadena Heritage and Pasadena Heritage have discussed the need to preserve Altadena’s history by planning out a rebuild with input from locals. And grassroots efforts have emerged to band residents together. Freddy Sayegh, who grew up in Altadena, has spearheaded a coalition to bring residents with different expertise and backgrounds together to create a plan.

“We know what we want. We know how we want to build,” he said at a recent Zoom meeting of about 200 people. “Who says we can’t have the finest architectural homes? Who says we can’t have the best cafes … who says we can’t be a clean, modern, yet historic city?”

The Eaton fire cut a brutal swath through Altadena and a cherished way of life in this eclectic foothill community it upended.

Sigler believes that those whose lives have been rooted in Altadena are the ones who will shape its future.

“What makes this place special is its people,” she said. “We definitely don’t want to be a group of architects telling the community how we think they should rebuild — we’ve always really felt that it should be the other way around.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.