2005 Pulitzer finalist | Feature Photography

Photograph of Lance Cpl. James Blake Miller taken on Nov. 9, 2004 with his Marine unit as they mounted an assault on the insurgent stronghold of Fallouja, Iraq. The image was published on the front pages of more than 150 newspapers and widely viewed on television and the internet. A country boy from Kentucky, Miller became an icon of the war. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Luis Sinco of the Los Angeles Times for his iconic photograph of an exhausted U.S. Marine’s face after a daylong battle in Iraq.

A member of Charlie Company of the First Marine Division, Eighth Regiment, watches out for enemy snipers amid the rubble of buildings in downtown Falluuja, Iraq. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Amid the rubble I photographed two dead insurgents, their arms above their heads and legs apart. They looked like boys sprawled on the beach. A Marine stripped them of their munitions. The dead lined our path through a city in ruins. It was impossible not to witness the carnage. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The reasons for his wartime involvement became fuzzier. Miller wondered if his conviction was worth innocence lost. He had nightmares and hallucinations. Sometimes, I wonder if Miller is still walking on the edge trying to discern friend from foe. Three years have passed since the fight in Fallouja. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

After another sleepless night, Miller starts his day with a cigarette at his apartment in Pikeville, Ky. “He’s not tha same as before,” says his wife, Jessica. “I’d never seen the anger, the irritability, the anxiety.” (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Miller had been diagnosed with PTSD in late 2005 but had not yet received psychological treatment six months later when he renewed his wedding vows to Jessica and prepared for an upcoming visit to Washington, D.C. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Miller and Jessica had grown up together. She performed with the high school dance team and he starred in three sports. In the flower of their youth they believed this was meant to be. I hope it works out, I said, at their nuptials. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

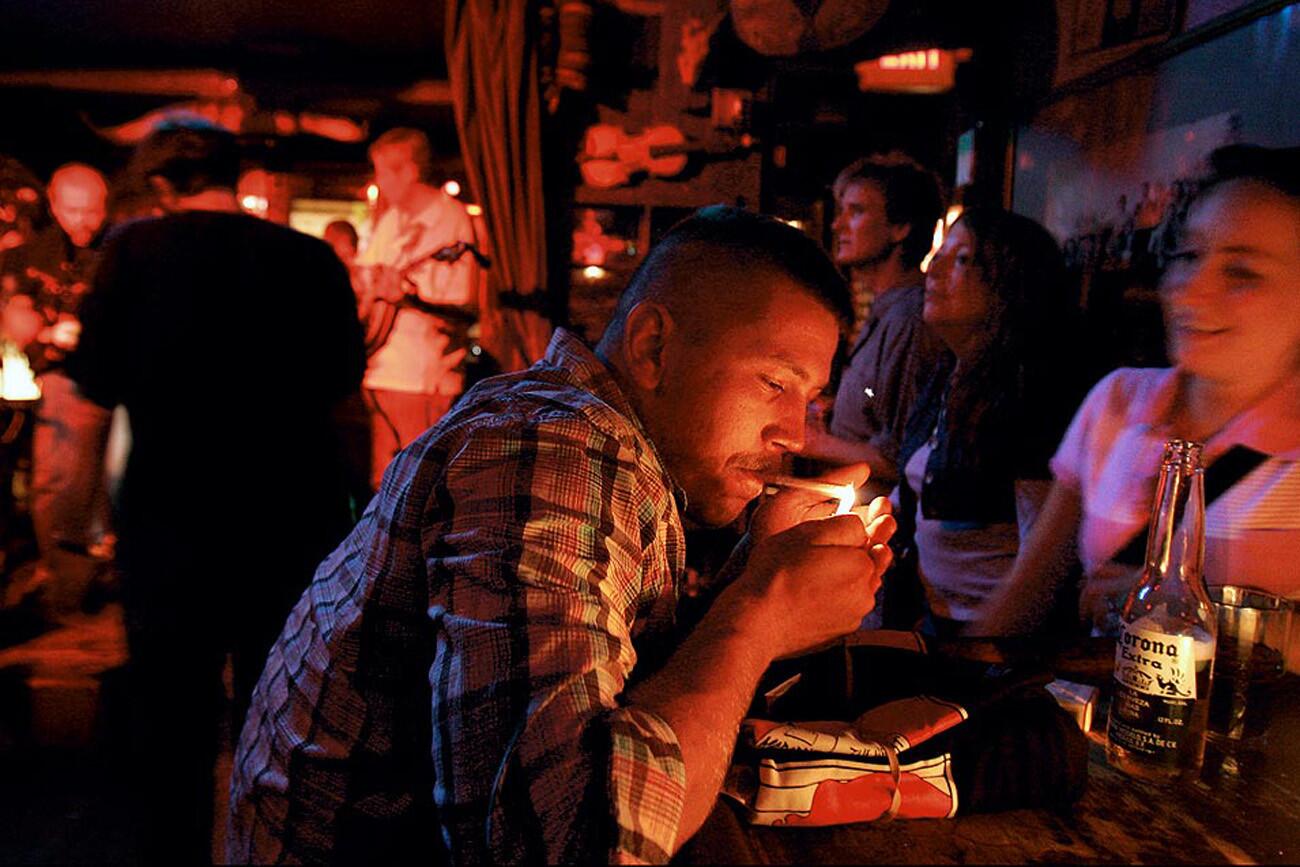

Miller lights up a cigarette in a bar. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

In the middle of an alcohol-induced blackout, Blake Miller supports himself on a parking meter in Washington, D.C. When strangers learn he is a combat veteran, they often offer free drinks and meals. Over time, he has received a multitude of gifts from people thanking him for his service. But Miller said he would gladly swap the trappings of fame for some peace of mind. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Distracted by the offer of free drinks for an All-American hero, Blake Miller stayed out until 3 a.m. and had a horrible hangover when he met with congressional representatives during a visit to Washington, DC. The trip to the capital was “a slap in the face,” Miller said. He had hoped to inform legislators about his battle with PTSD. The politicians thanked him for his service, but none promised to take up his cause or otherwise oppose the war in Iraq. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Blake Miller visited Washington, DC, to pick up an award from the National Mental health Association, which honored him for speaking publicly about his post-traumatic stress disorder. He also met with key legislators on behalf of the association. After the ceremonies, Miller took a whirlwind tour past the White House and Lincoln Memorial. But his mind focused elsewhere. “Let’s get drunk,” he said. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

When he returned from Washington, DC, Miller’s mood inexplicably changed and he slipped into depression. He withdrew and spoke little. It surprised and dismayed Jessica. Then he filed for divorce. It had only been 10 days since they renewed their vows. It was a lavish ceremony paid for by donors who had heard about his struggle with PTSD. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Miller moved into a house for recovering veterans in West Haven. He gained clarity in counseling. But he became homesick and longed for Jessica. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

When he met with Dr. Laurie Harkness at the Errera Community Care Center, Miller began to talk about the things that weighed heavily on his mind. He related trying to commit suicide on the outskirts of Fallouja one day. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Blake and Jessica had talked while he was away in Connecticut and they believed their relationship could work. Jessica was overjoyed when they reunited. It was a new beginning. But the good times didn’t last. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Marriage counseling proved difficult with sessions often ending in stony silence. Blake and Jessica stopped talking. There was no life, no romance to their relationship. They stopped having sex. Then, Jessica moved out. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

At a recent gathering, Miller partied with his newfound friends. They drank beer and moonshine, then sang and danced late into the night. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Miller went to work at a motorcycle repair shop whose owner presides over the local chapter of a motorcycle club. He joined and took the moniker of “sniper.” The club is under constant scrutiny by law enforcement. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)